January 31, 2015 marks the 54th anniversary of the space flight of Ham Chimpanzee, who became the first ape in space. Save the Chimps marks this anniversary to honor Ham, his courage, and his unwilling sacrifice. The Space Chimps, or “Astrochimps”, hold a special place in the hearts of everyone at Save the Chimps. It was the plight of the Air Force chimps, the chimps used in the early days of space research, and their descendents, that inspired our late founder Dr. Carole Noon to establish Save the Chimps.

January 31, 2015 marks the 54th anniversary of the space flight of Ham Chimpanzee, who became the first ape in space. Save the Chimps marks this anniversary to honor Ham, his courage, and his unwilling sacrifice. The Space Chimps, or “Astrochimps”, hold a special place in the hearts of everyone at Save the Chimps. It was the plight of the Air Force chimps, the chimps used in the early days of space research, and their descendents, that inspired our late founder Dr. Carole Noon to establish Save the Chimps.

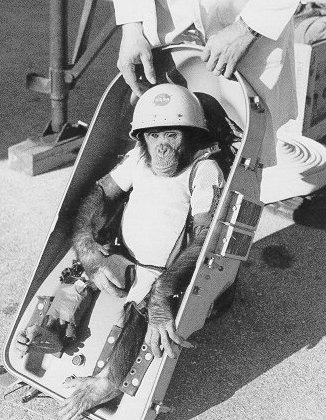

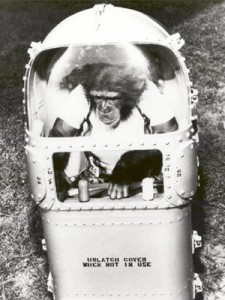

Ham’s story spans the globe and into the reaches of space. Born in Cameroon in approximately 1957, Ham was captured and brought to a facility in Florida called the Miami Rare Bird Farm. In July 1959, Ham was transferred to Holloman Air Force Base in Alamogordo, NM to be trained for space flight as part of Project Mercury. Ham at the time was known as Chang, or #65, and was renamed at the time of his spaceflight after the acronym for “Holloman Aero Medical.” Ham and other young chimps, including Minnie (the mother of two STC residents, Rebel and Li’l Mini) and Enos (the chimp who would become the first and only chimp to orbit the Earth), were habituated to long periods of confinement in a chair, and trained to operate levers in response to light cues. After 18 months of training, Ham was selected as the chimp whose life would be risked to test the safety of space flight on the ape body. On January 31, 1961, after several hours of waiting on the launch pad at Cape Canaveral, FL, 3 ½ year old Ham was propelled into space, strapped into a container called a “couch.”

Ham’s flight lasted approximately 16 ½ minutes. He travelled at a speed of approximately 5800 mph, to a height of 157 miles above the earth. He experienced about 6 ½ minutes of weightlessness. Incredibly, despite the intense speed, g-forces, and weightlessness, Ham performed his tasks correctly. After the flight, Ham’s capsule splashed down 130 miles from its target, and began taking on water. It took several hours for a recovery ship to reach Ham, but miraculously he was alive and relatively calm considering his ordeal. When he was finally released from the “couch” however, his face bore an enormous grin. Although interpreted as a happy smile by many people, Ham’s expression was one of extreme fear and anxiety. That fear was demonstrated again sometime later through an act of defiance. Photographers wanted another shot of Ham in his “couch.” Ham refused to go back into it, and multiple adult men were unable to force him to do so.

Unlike the rest of the space chimps, Ham was spared decades of biomedical research, but he did have a lonely existence for many years. He was transferred to The National Zoo in 1963, where he lived alone for 17 years, before finally being sent to the North Carolina Zoo where he could live with other chimps. He died 22 years after his historic flight into space, on January 18, 1983, at the estimated age of 26.

Ham’s flight is remarkable for many reasons. Ham not only survived the flight, but performed his tasks correctly, despite the rigors of space flight and the fear he must have experienced. His courage and heroism paved the way for Alan Shepard, Jr., the first American in space. But perhaps the most remarkable aspect of this story is often lost in all of the writings about Ham: he was a baby. If Ham had not been kidnapped and his mother killed, he still would have been nursing at age 3 ½, dependent on his mother for survival. “We should never forget that the individual strapped aboard that capsule 50 years ago today was, in fact, a child,” says STC Sanctuary Director Jen Feuerstein. “I can’t imagine a human toddler performing so admirably under the conditions that Ham endured. It says a lot about Ham’s character, intelligence, and bravery.”

Today we honor and remember Ham and all of the young chimps who suffered through the tragic deaths of their mothers and the transatlantic journey to the United States to become test subjects for space flight. Although Ham had no children, Save the Chimps is proud to have provided a peaceful retirement for other survivors and descendents of the space chimp program.

As Dr. Carole Noon once said, “They have bravely served their country. They are heroes and veterans.”